Photographs and Holograms from the Haystack Radio Observatory

Debra Balken

Today the function of the artist is to bring imagination to science and science to imagination, where they meet, in the myth.

Cyril Connolly, "The Unquiet Grave"

Unlike the utopian ethos of many modernist artists who have turned to technology as both a subject and device, Susan Gamble and Michael Wenyon have always remained disaffected of the giddy overtones of these idealistic gestures. While the work of the Russian Constructivists, and later figures such as Naum Gabo and Antoine Pevsner, might have spawned (perhaps unwittingly) a widespread, yet frequently esoteric, implementation of science-based materials in the arts, Wenyon & Gamble have consciously dissociated themselves from these visionary pursuits. Rather than being seduced by technology's gambit––its magical and spectacular products––this collaborative artistic team has been drawn to the history of science, specifically, since 1986, to the study of astronomy and its practitioners, findings, innovations and instruments. From this distanced stance, they have come up with a more analytic, conceptual take on the imagery of science, one which reveals both its elegance and connections with art.

In fact, when Wenyon & Gamble became artists in residence at the Royal Greenwich Observatory, Sussex in 1987, they had already made a decision to avoid any of the obvious or flashy representations of contemporary science, believing the history of the field could be mined more effectively for visual content. As both artists have said, "instead of being 'inspired'`by the latest imagery of 'big science', we would go back to the days when individuals struggled with hand-made equipment, half hoping to discover a way to make gold.1 …

While both artists also pursued a residency at The Royal Observatory in Edinburgh in 1994 … they came to feel a need to move away from what they have described as "historical science to contemporary science."3 The shift was part of a growing recognition of the consumerist dimension of science, its zeal and constant necessity to outpace the ongoing obsolescence of equipment and instruments. As they felt that, "going backwards in time to find 'sources' for our images seemed like a way to subvert or at least frustrate the utopian art-science construction4, this focus became delimiting, or at least, in need of revision or redirection as their understanding of the culture of science extended to its voracious requirement for new technology.

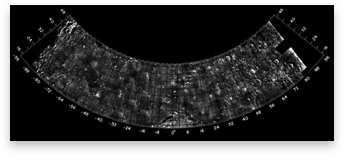

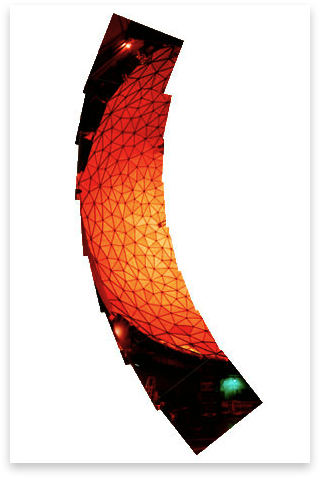

…The Haystack Radome, Mapped with Its Own Telescope, 2000 … is a single, splayed, longitudinal view of the surface of the dome, which when flattened in this digital format becomes a mosaic of geometric patterns. Similarly, The Dish Lensed, Haystack Observatory, 2000, reveals the enormous dish of the telescope skewed against the backdrop of the tiles of the dome to be a luminous, floating, ambiguous object rather than as a contraption or mere technological device. These images are replete with the grandeur of science but they are also, ironically, transformative, recasting clinical spaces and machines into imaginary, and sometimes ethereal, environments.

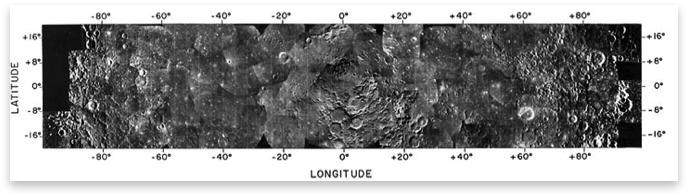

Wenyon & Gamble have noted that a primary architecture underlies and unifies both the mapping of the moon and their own photographic reconstructions of the radome. They have found that "from...examination of these astronomical mosaics and the mathematical relationships we construct our own projections and reflect upon the architectonic nature of seeing."6 A certain geometry or symmetry, then, emerges from both photographic investigations, the difference resting on the issue of use––the Apollo shots of the moon have been designated as scientific documents; Wenyon & Gamble's images are defined as art. But unlike astronomy, these artists have also played with this basic geometry, working it to elaborate and metaphoric ends. In Rotational Mosaic, Haystack Dome, 2000, for example, an exterior view of the radome is engulfed by images of clouds configured as a concentric pattern. While the shape of this 'mosaic' of photographs echos that of the dome, it also alludes to the quest of astronomy and its study of celestial bodies.

… While works such as Rotational Mosaic, Haystack Dome and Dome Explored in Lunar Form might allude to the metaphorical dimensions of science, these artists's images of the machines or technological apparatuses at the Haystack Observatory reveal the practice of astronomy to be a highly methodical pursuit. The banks of computers and recording devices that are featured in The Correlator, Haystack Observatory, 2000 and The Control Room, Haystack Observatory, 2000, while rendered with the same broken or multitudinous perspective system that structures The Dish Lensed, Haystack Observatory, are dead-pan representations that demystify the industry of science and its fetishistic dependence upon equipment.

…

Notes:

- Michael Wenyon, electronic mail letter to the author, August 11, 1999.

- Susan Gamble and Michael Wenyon, In the Optical Realm: Wenyon & Gamble, Holographic Installations, 1988-91, ex. cat., Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton Art Gallery, 1991

- Wenyon, electronic mail to the author, August 11, 1999.

- Ibid.

- Susan Gamble and Michael Wenyon, "Observing–How we are all scientized now," proposal for forthcoming paper at the College Art Association annual meeting, February 2000.

- Ibid.

- Gamble, electronic mail to the author, August 13, 1999.

Excerpt [1220 words from 2,332 words] of the essay by Debra Bricker Balken in Observing the Observers… , the catalog to the exhibition by Wenyon & Gamble at the MIT Museum Compton Gallery, February 18 – May 6, 2000. ©2000 Debra Bricker Balken, all rights reserved.

To purchase the catalog, please contact the MIT Museum shop by email at mitshop@mit.edu

To purchase the catalog, please contact the MIT Museum shop by email at mitshop@mit.edu