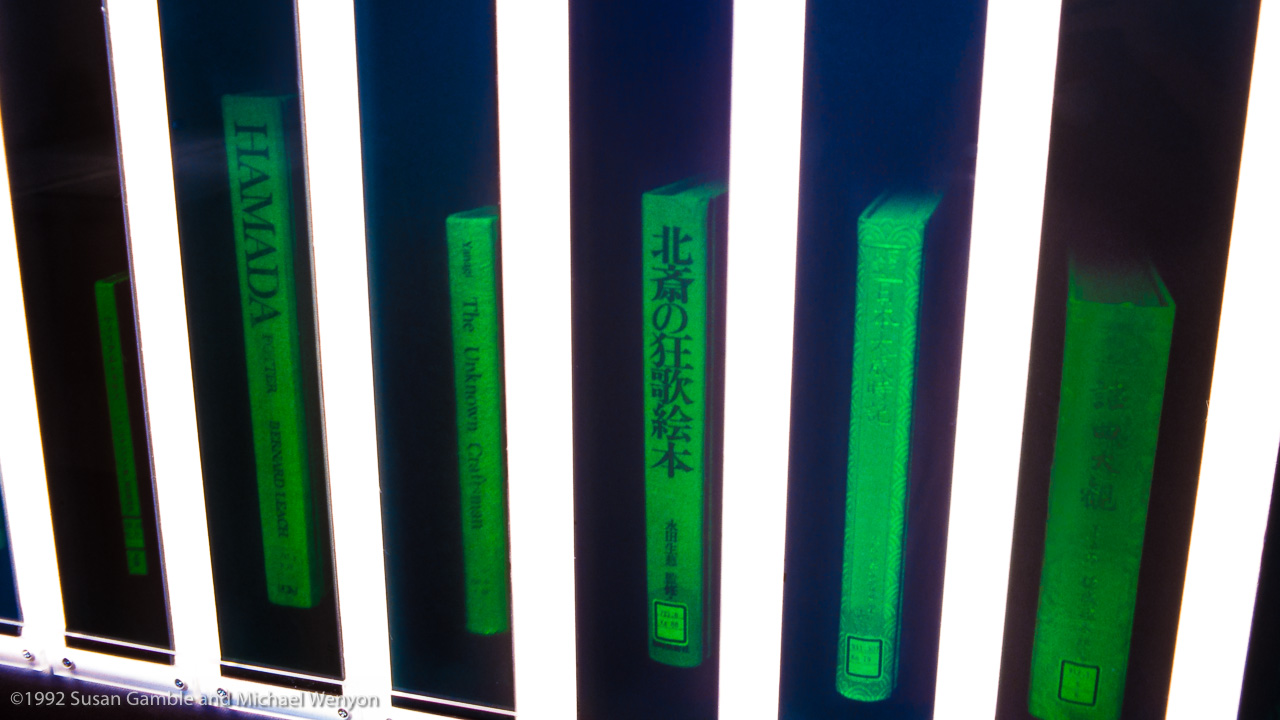

Bibliography, Wenyon & Gamble, Art Tower Mito, Mito, Japan (1992), 54 holograms of books, selected from the Art Library of the University of Tsukuba, Japan

The book has always been a treasure house of human knowledge, and its binding a beautiful craft object. For example, there are very decorative sacred books inlaid with jewels, silver and gold.

But however profound the content of a book, if you are unable to decipher the code of the language it is written in, you are not able to read it. In fact, you cannot read a book from an unknown culture (I cannot read an Arabic book), or a book in a dead language such as the hieroglyphic books of ancient Egypt.

On the other hand, a book, which is a physical object, stimulates our sense of ‘fetish’ regardless of its language. This is as true of an ordinary book in a shop as it is of the richly-bound books of kings and princes.

So we collect books, displaying them on bookshelves, looking at their spines and, in many cases, feeling as if we own their wisdom, even if we never read them all.

Now, with the works of Wenyon & Gamble, we can see an image of the spine of a book in a screen shaped like a tanzaku (a paper strip for writing Japanese poems). These artists have found their books in a university library, their interest aroused by the books’ contents, or their covers, or simply their titles. These images show a three-dimensional space ‘contained’ in a two-dimensional surface, but it is not fixed like an ordinary picture or photograph––this holographic image changes as we change our position.

So, we feel as if there is a real book contained in the hologram, and we want to go around behind it. But, of course, that is impossible because all we find is the back side of a thin sensitized glass plate.

As I say, no matter how important the contents of a book, if you cannot decode its language, that book is no more than a sheaf of papers. Then our frustration with these holographic images––that we cannot touch them, even though they look like real books––is reminiscent of the difficulty we can have in absorbing information contained in a book. Perhaps they express visually the hardships these artists experienced, and the importance they attached to, communicating with the ‘exotic’ culture of Japan.

And since the skill of holography itself still requires professional knowledge and equipment, so in this work, whose material is untouchable and unreadable (for those who cannot even read the language of the spine), the book is a symbol of some kind of ‘sealed knowledge’ between contemporary peoples who have lost their common code.

Toshihiro ASAI

Curator, Art Tower Mito, Contemporary Art Gallery

(translated from the Japanese)

But however profound the content of a book, if you are unable to decipher the code of the language it is written in, you are not able to read it. In fact, you cannot read a book from an unknown culture (I cannot read an Arabic book), or a book in a dead language such as the hieroglyphic books of ancient Egypt.

On the other hand, a book, which is a physical object, stimulates our sense of ‘fetish’ regardless of its language. This is as true of an ordinary book in a shop as it is of the richly-bound books of kings and princes.

So we collect books, displaying them on bookshelves, looking at their spines and, in many cases, feeling as if we own their wisdom, even if we never read them all.

Now, with the works of Wenyon & Gamble, we can see an image of the spine of a book in a screen shaped like a tanzaku (a paper strip for writing Japanese poems). These artists have found their books in a university library, their interest aroused by the books’ contents, or their covers, or simply their titles. These images show a three-dimensional space ‘contained’ in a two-dimensional surface, but it is not fixed like an ordinary picture or photograph––this holographic image changes as we change our position.

So, we feel as if there is a real book contained in the hologram, and we want to go around behind it. But, of course, that is impossible because all we find is the back side of a thin sensitized glass plate.

As I say, no matter how important the contents of a book, if you cannot decode its language, that book is no more than a sheaf of papers. Then our frustration with these holographic images––that we cannot touch them, even though they look like real books––is reminiscent of the difficulty we can have in absorbing information contained in a book. Perhaps they express visually the hardships these artists experienced, and the importance they attached to, communicating with the ‘exotic’ culture of Japan.

And since the skill of holography itself still requires professional knowledge and equipment, so in this work, whose material is untouchable and unreadable (for those who cannot even read the language of the spine), the book is a symbol of some kind of ‘sealed knowledge’ between contemporary peoples who have lost their common code.

Toshihiro ASAI

Curator, Art Tower Mito, Contemporary Art Gallery

(translated from the Japanese)

It is a great pleasure for us to present this work in Mito. From April 1990 to March 1992 we were teaching in Tsukuba and we visited ATM many times. We also used to enjoy visiting nearby Mashiko, the home of Shoji Hamada. The book of Hamada by Leach we found in the library at Tsukuba.

When we first arrived in Japan to live, we knew that we wanted to make work that acknowledged our new location. We wanted to engage with Japanese culture, but not by repeating exotic clichés. This is difficult, because of language and because we must always look from our own cultural position, which cannot be neutral. But books communicate between cultures, they are a physical object that passes through a magic window in the transfer between two peoples. They can be misunderstood, they can be misinterpreted, but they are always the same object, insulated from individual perceptions.

Susan Gamble

Michael Wenyon

September, 1992

When we first arrived in Japan to live, we knew that we wanted to make work that acknowledged our new location. We wanted to engage with Japanese culture, but not by repeating exotic clichés. This is difficult, because of language and because we must always look from our own cultural position, which cannot be neutral. But books communicate between cultures, they are a physical object that passes through a magic window in the transfer between two peoples. They can be misunderstood, they can be misinterpreted, but they are always the same object, insulated from individual perceptions.

Susan Gamble

Michael Wenyon

September, 1992