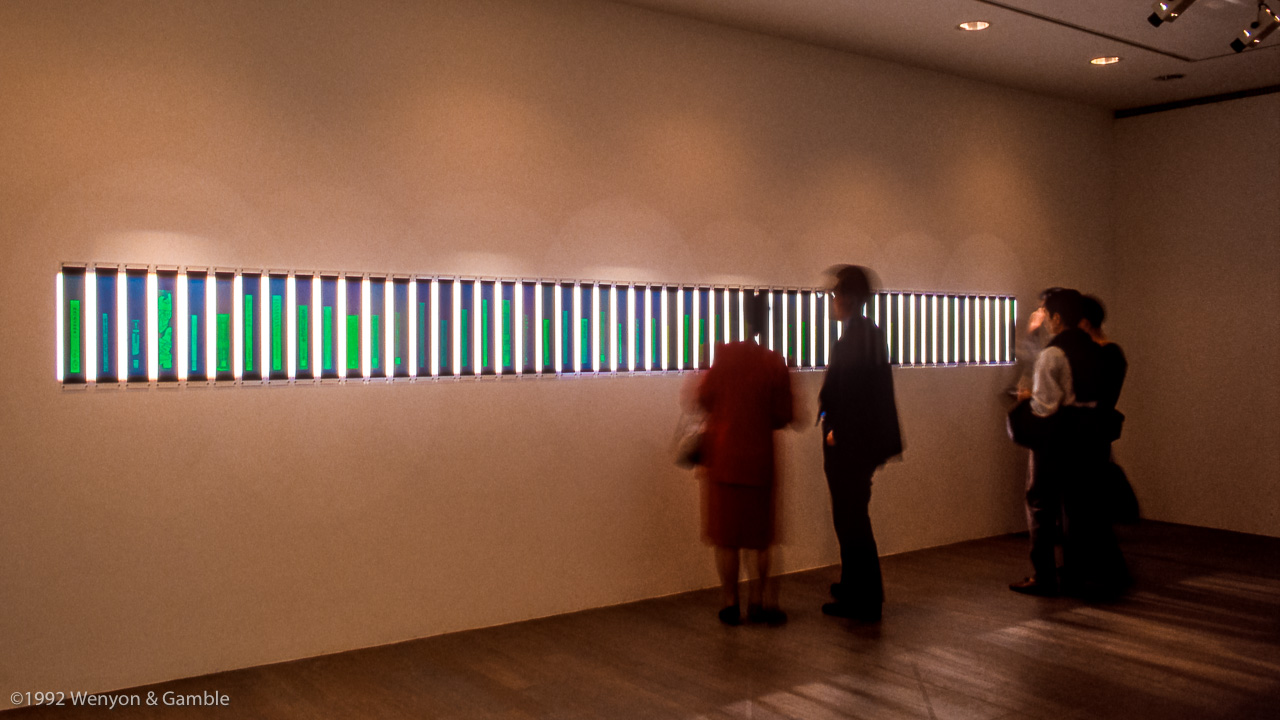

Bibliography, Wenyon & Gamble, Art Tower Mito, Mito, Japan (1992), 54 holograms of books, selected from the Art Library of the University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan

Bibliography, 1991–92

Wenyon & Gamble

Michelangelo is said to have spent months in the quarries of Carrara, unable to tear himself away from the sight of all the marble blocks in which he saw the shapes of works without number waiting to be liberated. The scholar's quarries are libraries. His form of indulgence is the reading of catalogues of second-hand books which, to his mind, conjure up visions of curious lore and possible clues to the riddles of the past. But there is at least one thing in common between art and scholarship: both may appear to be utterly useless--as useless in fact, as are all dreams and memories

E.H. Gombrich, 'Meditations on a Hobby Horse, Art and Scholarship', Phaidon, London, 1963, p106

During a period of teaching at Tsukuba University in Japan, we found the art library there full of Japanese texts that we could not begin to read, sitting on the shelves next to books in English and other European languages. It was a peculiar combination of the strange and the familiar. In this foreign library we felt like tourists searching for the exotic sights. We were scholars, of a new language and culture, looking for points of contact and struggling to understand new forms.

The arts of the past are an important strand in the memories of mankind, and long may they remain so. Shrines, monuments, and images remain in front of everybody's eyes when books are forgotten and documents buried in archives.

E.H. Gombrich, ibid, p108

In the United States, a National Research and Education Network proposal exists to build a three-billion-bits-per-second communication network over high speed fiber optic cables, with computers that can transmit the entire Encyclopedia Britannica in a second. This project should be completed in 1995 and will connect major universities and research institutions.

Language is not an organization of natural stimuli, like a beam of photons; it is an organization of stimuli realized by man, and as such, an artifact, like any other art form.

Umberto Eco, 'The Open Work', Hutchinson Radius, London, 1989, p28

Technology promises access to information without the need to see or handle a book: yellowing books and documents can have their contents scanned in digital form onto optical discs. Perhaps the need for a printed page as the original form of any text will ultimately disappear. The book itself may change, take on a new form, perhaps losing the aesthetic character we now know. An old and fading book has a sentimental quality, having passed through many hands -- surviving not only time but constant changes in the pattern of ideas. Accessing information through networks will remove the physical contact with text and language as an object.

We are coming to the end of the culture of the book. Books are still produced and read in prodigious numbers, and they will continue to be as far into the future as one can imagine. However, they do not command the center of the cultural stage. Modern culture is taking shapes that are far more various and more complicated than the book-centered culture it is succeeding.

O. B. Hardison Jnr, 'Disappearing through the Skylight: Culture and Technology in the Twentieth Century',

Penguin Books USA, 1989, p264

This seemed an appropriate moment to consider the role of the book as a vulnerable artifact in late twentieth century culture. We decided to extend our cultural exploration of the library to the making of our art. The library at Tsukuba University would define a convenient boundary to our enquiries, its holdings of books providing the context to consider our own position as students of Japanese culture.

We were interested in recording books as three-dimensional objects in holograms. The idea of a holographic recording of a book seemed mysterious in itself, throwing up questions we were keen to explore and resolve. During 1991 and 1992, we produced 127 separate holograms, each depicting a single book.We used a straightforward documentary form of hologram to record individual books. The technique was developed in the former Soviet Union solely for the documentation of objects, and used in museums there to record and display valuable items that might otherwise not be shown. It is called the Denisyuk hologram after the scientist who invented it.

We were interested in recording books as three-dimensional objects in holograms. The idea of a holographic recording of a book seemed mysterious in itself, throwing up questions we were keen to explore and resolve. During 1991 and 1992, we produced 127 separate holograms, each depicting a single book.We used a straightforward documentary form of hologram to record individual books. The technique was developed in the former Soviet Union solely for the documentation of objects, and used in museums there to record and display valuable items that might otherwise not be shown. It is called the Denisyuk hologram after the scientist who invented it.

Bibliography and Scroll, installation at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 1992, 54 holograms of books, and two large-format laser prints in acrylic display cabinets

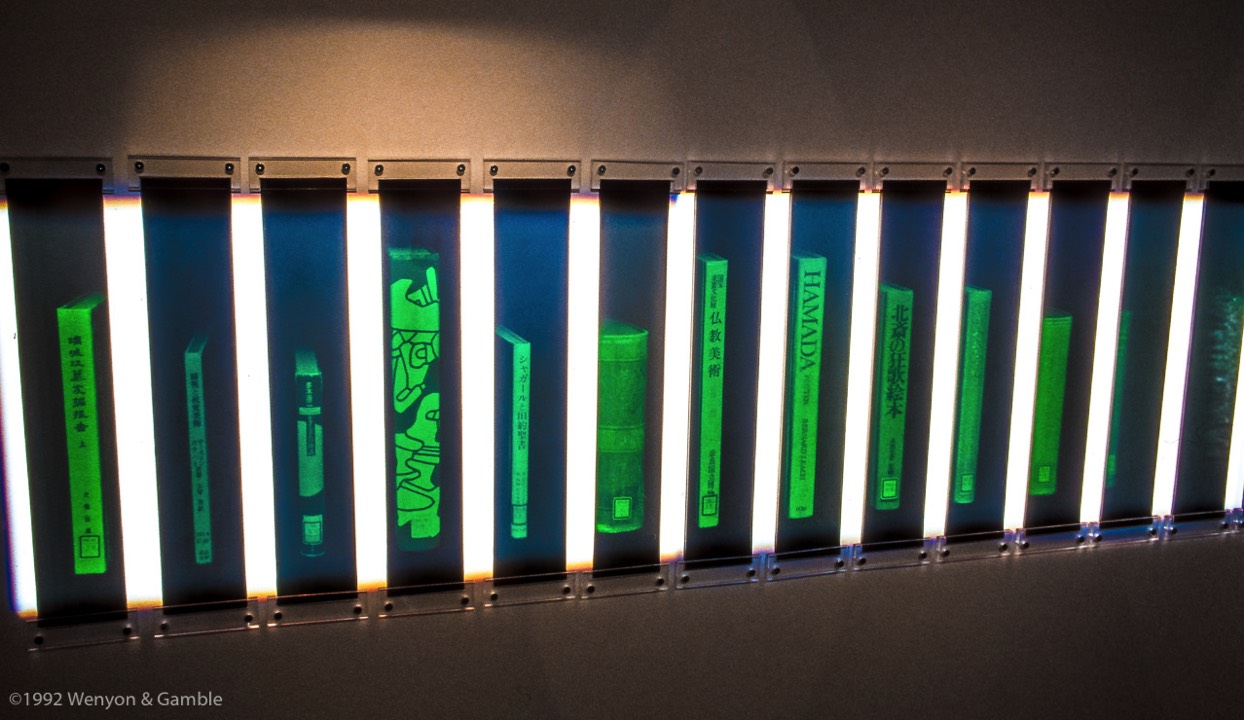

The Denisyuk hologram records an object placed directly in front of a photographic film or glass plate. The object may even touch the emulsion at one point. The emulsion is clear, or as clear as the manufacturer can make it, so that the object can be illuminated from behind the film or plate by light transmitted through it. The resulting image can be very beautiful, exploiting the hologram's potential to record details and texture at high resolution as well as the 'play of light' that animates a real object as a viewer moves past it.

The subjects of the books in Bibliography, the final work, vary from old Japanese texts on astronomy to contemporary art criticism. Their selection was not random, but followed certain definite -- though varied -- principles. Although we could not read titles in Japanese Kanji characters, we chose Japanese books with as much care as those in the English language.

The subjects of the books in Bibliography, the final work, vary from old Japanese texts on astronomy to contemporary art criticism. Their selection was not random, but followed certain definite -- though varied -- principles. Although we could not read titles in Japanese Kanji characters, we chose Japanese books with as much care as those in the English language.

The scholar is the guardian of memories.

E. H. Gombrich, ibid, p107

Although the contents of the books in Bibliography are known to us, from now on they can only be seen; in their present form, none of the books are readable. There is a strange, perhaps private, pleasure in knowing that within our holographic book images lie so many inaccessible two-dimensional representations of the three-dimensional world.

Scroll, 1992–93

Scroll, a new work made for this exhibition, evolved in Japan during our work on Bibliography and is related to it in both form and content. In 1990, on a visit to the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto, we saw a scroll of drawings by Bernard Leach. We were interested to see a western artist's appropriation of this Japanese form and in particular we liked the glass weights that held the scroll open. We initially credited Leach with this device but, unknown to us at the time, nearly all Japanese museums display scrolls in this way. The ancient form of the scroll has reappeared again with recent technologies. We scroll through text on a computer, and fax machines spew out long scrolls of paper. A scroll can have a strong physical presence: a museum display of a major work of Japanese literature, for example, takes up a large space laid out in its entirety. Making these connections we became interested in pursuing this form again in our work. Over the past few years we have fabricated, or drawn, invented texts and book pages using computer programmes designed to manipulate photographic imagery for desktop publishing. These drawings contain a random face of text in which the printed words become abstract, reduced to a graphic symbol or texture. In Scroll the computer drawings are combined with holograms of books similar to those in Bibliography. The holograms are placed on the scrolls of computer-derived pages in the manner of a Japanese Museum display.

From the catalog to Volumes, an exhibition of holograms by Susan Gamble and Michael Wenyon at the Photographers' Gallery, London, 28 May to 24 July, 1993. Published by The Photographers' Gallery, 5 & 8 Great Newport Street, London WC2H 7HY, ISBN 0 907879 381, editor David Chandler

©1993 the authors and The Photographers' Gallery

©1993 the authors and The Photographers' Gallery